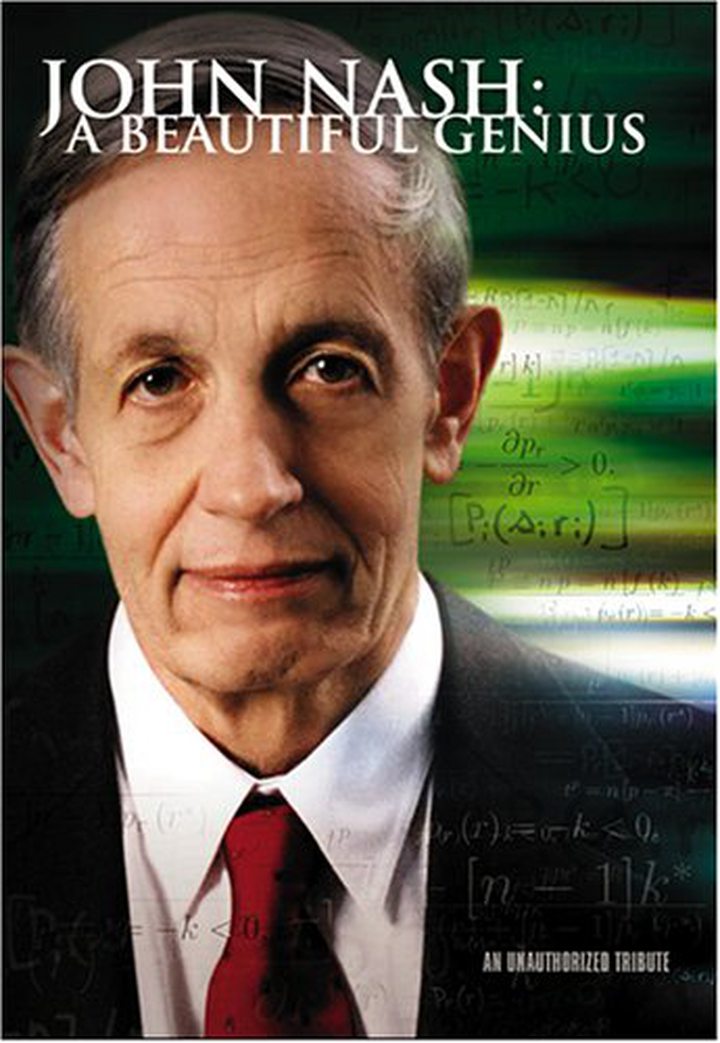

John Nash, ‘A Beautiful Mind’ That Changed Economics, Dies With Wife in Crash

Their combined struggles with his mental illness were documented in the book, “A Beautiful Mind,” which was later transformed into an award-winning movie starring Russell Crowe.

The death of the couple together, friends related, was a sad and poignant epitaph to a unique modern love story.

The famed Nobel-prize winner and Princeton University scholar and his wife were killed when a taxi carrying them slammed into a guardrail on the New Jersey Turnpike, ejecting and killing both. He was 86 and she was 82.

Mr. Nash was the father of what is known in economics as the “Nash Equilibrium,” a state where rivals in a game, a negotiation or a competition can’t advance their gains by changing their positions and thus reach a steady state.

Emerging in the late 1940s—an era when the Cold War and growing nuclear arms race between the U.S. and Soviet Union put high stakes on negotiating strategy—his ideas enlivened the field and reached far beyond the cold and obscure calculus of advanced mathematics. Economists applied the ideas further to industrial organization and trade negotiations.

“I once said that if John got a dollar for every time someone talked of or used ‘Nash equilibrium,’ he would be a very rich man,” Avinash Dixit, an economics professor emeritus at Princeton University and friend of Mr. Nash for more than two decades, said in an email exchange Sunday shortly after hearing about the couple’s death.

Mr. Nash suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, which sidetracked his career and marriage for long stretches after he wrote his groundbreaking 32-page Princeton thesis on game theory at the age of 21. He earned his doctorate at Princeton at the age of 22 in 1950.

“The mental disturbances originated in the early months of 1959 at a time when Alicia happened to be pregnant,” Mr. Nash reflected in an autobiography published by the Nobel Foundation after he won the highest prize in economics in 1994.

The two divorced years after his schizophrenia emerged in full force and were remarried in 2001, according to Sylvia Nasar, author of “A Beautiful Mind.”

Mr. Nash spent much of his adult years in psychiatric institutions, managing medications to address the disease, or wandering city to city in Europe or the Princeton campus, where students sometimes described him as a phantom.

“At the present time I seem to be thinking rationally again in the style that is characteristic of scientists,” Mr. Nash wrote in his 1994 commentary for the Nobel. “However this is not entirely a matter of joy as if someone returned from physical disability to good physical health. One aspect of this is that rationality of thought imposes a limit on a person’s concept of his relation to the cosmos.”

Life for both gradually turned around after the award.

“At the end of the Nash’s wedding ceremony in 2001, when they remarried after divorcing…I asked John to kiss Alicia again so I could take a picture,” Ms. Nasar reflected Sunday. “He looked up and said. ‘A second take? Just like the movies.’”

“He stayed active in research, and was invited to speak at many universities and conferences,” Mr. Dixit said of Mr. Nash’s later life and career. “One of his interests during this period was inflation, specifically alternative monetary systems to ensure a stable price level.”

His work would touch on other areas of math which proved central to finance, including the pricing of derivatives securities, Mr. Dixit said. For that work, on nonlinear partial differential equations, Mr. Nash last week received the prestigious Abel Prize in Oslo from the king of Norway for outstanding work in mathematics.

John Nash was born in Bluefield, W.Va., in 1928, his father an electrical engineer and mother a school teacher. He was precocious from a young age, developing as a high-school student proofs of the famous “Fermat’s theorem,” which related to the behavior of integers when multiplied by themselves. He earned undergraduate and master’s degrees at Carnegie Tech—now Carnegie Mellon University.

Game theory and the introduction of mathematics to economics were hot areas when he arrived as an eccentric graduate student at Princeton in 1948. Two Princeton professors, Oskar Morgenstern and John von Neumann, had lit a fire with a book called, “Theory of Games and Economic Behavior.”

Mr. Nash extended their work. A decade later Fortune Magazine singled him out as a rising star in the hot new field, just as his disease began to set in, according to Ms. Nasar’s accounts.

“His papers have a celestial and effortless quality, as if penned—coolly—while God murmured in his ear,” Dilip Abreu, a Princeton game theory economist, said Sunday.

Driving in New Jersey Saturday, Mr. Nash’s taxi driver, Tarek Girgis, attempted to pass another car, according to New Jersey State Police Sgt. Gregory Williams. The driver lost control, crashed into a guardrail and then hit another car. An investigation into the crash is ongoing, though there is nothing suspicious about the nature of the accident, the officer said.

“What a horrible way to die,” Mr. Dixit said. “But perhaps better to go together, suddenly, and at a time of triumph after the big prize, than the way far too many people go—after a long chronic illness, or after years of a degrading nursing home existence.”

Ms. Nasar described Alicia Nash as “the rock on which he rebuilt his life.” Their death together, she said, was emblematic of their lifelong bond.

“John and Alicia’s lives experienced the extremes of human experience—genius and madness, obscurity and fame—together,” she said. “Nash’s story wasn’t only about the mystery of the human mind, it was also a love story. A very grown up love story.”