Vanuatu Disaster: the Island Hit by an Earthquake, a Volcano then Cyclone Pam

This almost biblical run of misfortune happened within the space of just a few weeks to the small Vanuatu island of Ambrym.

But on Tuesday villagers here were counting themselves lucky.

The first visit by outsiders since the cyclone struck has revealed a battered community but, remarkably, homes have mostly remained intact and there have been no reported deaths. That is not to say there is no concern among the 7,000-strong population.

The storm has flattened the subsistence crops they rely on for food and regular supplies from other islands have dried up as the cleanup after the storm begins.

A former Melbourne builder, Ian Walter, arrived at Ambrym’s airstrip on Tuesday with his own personal aid package, including saws and bags of rice for the village of Wuro.

The BuildAid founder began construction last July of a school here to serve a number of villages. He said food supplies after the storm had been wiped out and the remaining crops would last “probably a week”.

“We had a 6.5 earthquake two weeks ago, followed by the volcano erupting again for the first time in 100 years and now a category five cyclone,” Walter said. “It was better than I expected, not as damaged as it could be, and I think more south of Vila down to Tanna is probably 10 times worse than here.”

Indeed aid agencies report a “totally different scale of destruction” to the south of Ambrym and to the island of Tanna, whose population of 30,000 is scattered in pockets across a volcanic outcrop.

World Vision staff, who with Red Cross and Care International are on the ground delivering immediate relief, report devastation, the agency’s Vanuatu spokeswoman Chloe Morrison said.

“In forests, there’s not a single leaf on the trees,” she said. “Similar to Port Vila [Vanautu’s capital], shanty-like villages were just totally decimated and blown away. Unlike Port Vila, there are very few structured buildings left and a lot of people have lost their homes.”

It is the capital, where six people were killed, and Tanna, where five died, that account for the official death toll of 11, according to Vanuatu’s lands minister, Ralph Regenvanu.

The UN revised its death toll from Vanuatu’s worst natural disaster downwards from 24 – a number hotly disputed by the Vanuatu government in a sign of a potential rift.

Regenvanu said the UN’s initial toll was “crazy” and would probably prompt his government to demand an explanation. “Our’s is 11,” he said. “I don’t know where they got 24 from. That’s just crazy stuff. We’ll be approaching them about that.”

Vanuatu would also soon be making formal approaches to countries for longer term disaster recovery assistance, Regenvanu said. “We’re still in the early-response phase. We’re definitely going to need a lot more for recovery. That’s a whole other ball game.”

In the meantime, the entire provinces of Tafea and Shefa, which encompass both the capital and Tanna, were the focus of the government’s immediate concern, Regenvanu said.

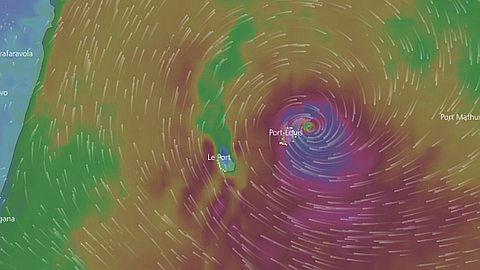

“Those are are the other places that as far as we know from the cyclone were most affected. Penama as well but we know the cyclone passed directly over Shefa from the tracking and there’s been a bit of aerial recon as well which has confirmed it’s pretty bad.”

For the population of Port Vila, the emphasis is on the recovery and remembering those who died.

In a church in the capital’s northern suburbs, the pastor, Willy Yannick, saw a baby he knew to be just week old die on the night of the cyclone.

Yannick told the Guardian the girl had died of exposure after her parents fled their destroyed house to shelter in Pakaroa Presbyterian church with dozens of other families.

“Her mother didn’t get to cover her up in a thick warm blanket. When they came here she was still alive. That night the storm cost her life.”

Yannick said more than 50 families continued to live at the church, with the reconstruction of their homes at least three months away. “All the houses have been blown away in this area,” he said.

No food has arrived from outside sources, save some tea and biscuits from the national disaster management office. “We need rice, meat – and tents so people can rebuild.”

While aid workers express relief at the comparative lack of death and destruction in some areas, they fear these are the communities who may be forgotten – just as they’re running out of food.

Ambrym may be one of those – despite its relative good fortune.

From the airstrip, the seaside village of Wuro lies at the end of a sandy path black with volcanic ash. The buildings, whether with roofs of corrugated iron or thatched plan leaves, are all intact. The men sit in the shade watching two elderly women comfort one man who has fallen ill and who will have to be taken to hospital on our return flight to Port Vila.

Linneth Tasso, 35, holding her one-year-old daughter, Catherine, says the storm was “very strong” and left her a “little bit” scared.

Asked about the damage to the garden, her brow furrows. “We need more food,” she says.